December 11, 2021

Nancy and I are big into museums. We absolutely love them, and it doesn’t really make much difference what the museum’s about; we’re interested in taking a look. Well, except maybe for museums devoted to dolls. Or clowns. Or clown dolls.

There were definitely dolls on display at the Deming Luna Mimbres Museum in Deming, New Mexico, when we visited, and some of them may well have been clown dolls. We didn’t stop at the exhibit to investigate. However, there was much more of interest to take a look at in this 20,000-square-foot museum skillfully managed by the Luna County Historical Society, and there’s something for everyone there.

About the name of the museum: it’s in the city of Deming (more about that later), in Luna County (and Deming is the county seat), and the Mimbres are a branch of the Mogollon culture, Native American peoples who lived in present-day southern Arizona and New Mexico from around 200 CE to when the Spanish arrived in the 1400s and 1500s. There are many cultural references to the Mimbres in this area.

Nancy and I agreed that, other than Harold Warp’s Pioneer Village in Minden, Nebraska, the Deming museum is one of the largest and widest-ranging local museums we’ve visited. If you’ve got an interest in Native American pottery, it’s got you covered. Want to see a lot – a lot – of geodes? You won’t be disappointed. Curious about early public schools in Deming? You’ll leave wiser for the experience. Fancy yourself a railroad aficionado? Hang on to your engineer’s cap. The museum’s website suggests arriving no later than 11 AM to ensure that visitors have plenty of time to see everything, and that’s sound advice.

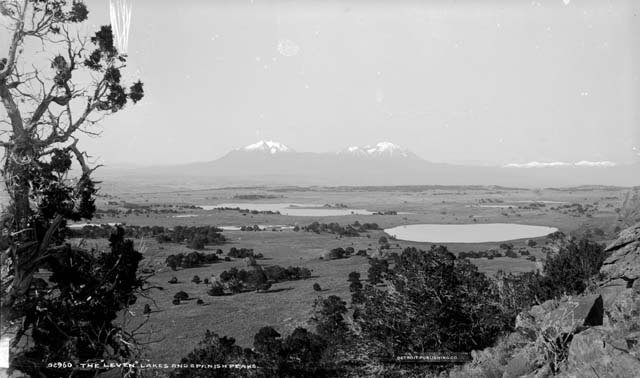

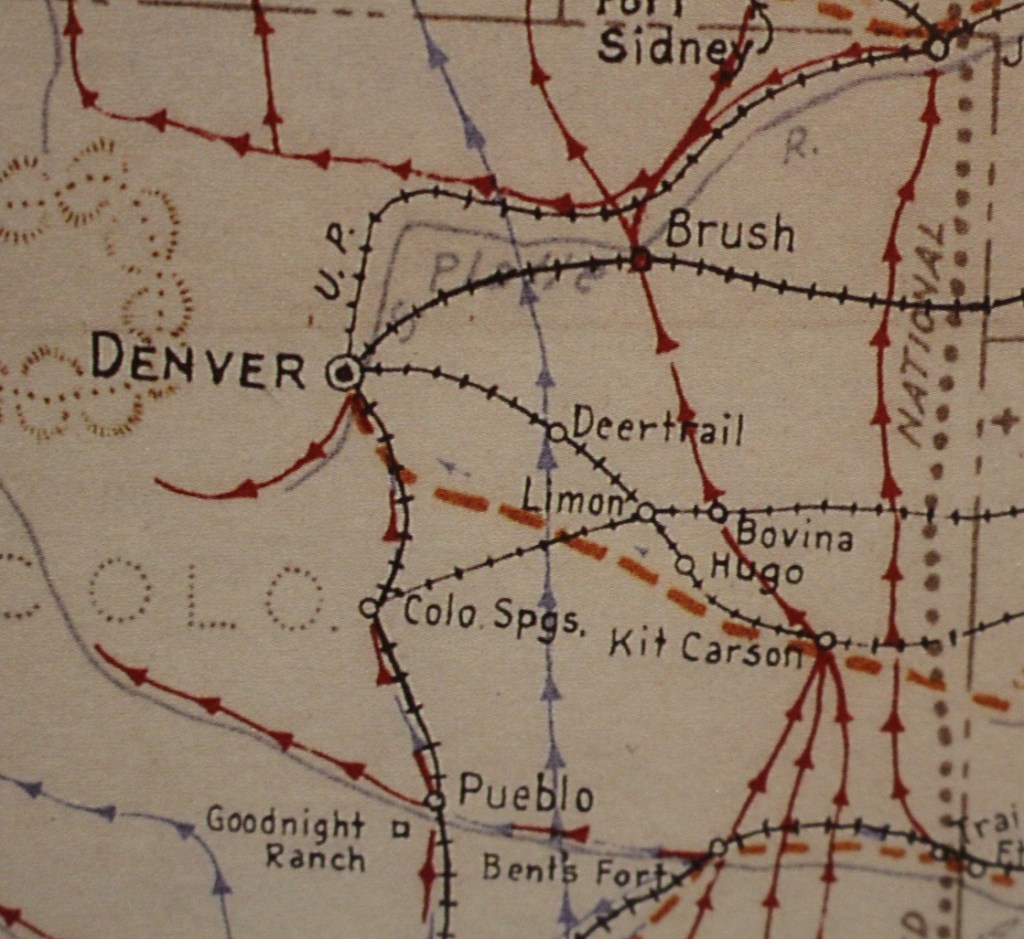

Let’s start with the railroads. The city of Deming lies within the Gadsden Purchase, a nearly 30,000-square-mile area in present-day southern Arizona and southern New Mexico that was acquired from Mexico in 1854 solely so that a southern U.S. transcontinental railway could be built. The city has historical ties to four different railroads:

- Southern Pacific Company, which began building a railroad from California to the Gulf of Mexico in the 1870s. The railroad reached Deming on Dec. 15, 1880.

- Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, which wanted to expand its line from Kansas City to the Pacific Ocean. The Santa Fe reached Deming on March 8, 1881, and by an agreement with Southern Pacific, established a new transcontinental railroad with the driving of a silver stake. Despite that ceremony, competition between the two lines for trade along the route remained fierce through the 1980s.

- Silver City, Deming & Pacific Railroad, which was incorporated in 1882 to transport copper ore from huge deposits in the hills about 50 miles north of Deming. A 48-mile narrow-gauge line between Silver City (silver was originally found in the area but that played out and was replaced by copper, which is still being very actively mined to this day) and Deming was completed on May 12, 1883. The Santa Fe bought the line in 1899.

- El Paso & Southwestern, incorporated in 1901, started a line intended to connect Deming with Douglas, Arizona, to move copper ore from the Bisbee, Arizona, area to eastern markets. Executives with EP & SW wanted the Southern Pacific and Santa Fe lines to compete for their business at the Deming connection.

Deming is named for Mary Ann Deming Crocker, the wife of Southern Pacific executive Charles Crocker. The city was originally 10 miles east of its current location; there wasn’t sufficient water at that first location, so the townsite was moved to the west to take advantage of the Mimbres River location.

The number of railroads, in addition to being a port of entry from Mexico into the United States, gave promoters at the time the fanciful idea that Deming would grow to be a huge metropolis. It was even given the nickname of “New Chicago.” That idea did not pan out (although Deming is really a lovely city, its current population is around 14,000).

Much of the popular culture around the “Old West” is centered on cattle drives and open range ranching. It’s said that two occurrences ended the open range period: horrific blizzards in the winters of 1887 and 1888, and the development of barbed wire. Although it had been initially developed a couple of decades prior, barbed wire wasn’t widely used until 1874, when Joseph Glidden, an Illinois farmer, developed a machine to make the fencing material efficiently. More than 500 U.S. patents were issued on different barbed wire patterns between 1868 and 1874. The introduction of barbed wire in the West allowed ranchers to keep their cattle in one area, but it also meant that migratory herds of buffalo weren’t able to move around. Barbed wire also, of course, had huge a impact on the Native American tribes that lived on the plains. There’s still a good deal of cattle ranching in the Deming area, at least in the areas that can be irrigated for pasture, and the museum has a nice little exhibit on barbed wire.

Writing of strong interests in very particular fields, the Deming museum has many display cases that contain thousands (I’m not exaggerating, and I may even be underestimating) of geodes. These rocks, which formed as bubbles in volcanic rock, contain a cavity that is filled with crystals, usually quartz. Rockhound State Park, a few miles south of Deming, is a great place to find lots of geodes. The ones that aren’t there are probably at the Deming museum.

Writing of rocks, there were a number of other different kinds of rocks besides geodes, including dinosaur fossils, petrified wood, and samples of other minerals from all around the world.

Enough with the rocks. The museum has on display a couple of firetrucks from Deming’s earlier days, along with a display of other firefighting equipment.

I didn’t take any pictures of it, but there’s a very nice display of some saddles, boots, chaps, and other equipment belonging to a locally famous rodeo cowboy from Deming who won a few bronco riding world championships in the 1950s and 1960s. He was asked in the 1980s, well after his retirement, what the difference between rodeo cowboys of the 1950s and the 1980s was and he replied, “Well, no one robs banks anymore.” I thought that was just hilarious.

The second floor of the museum, which we gradually discovered had previously been a full-size basketball court, had many more exhibits from Deming’s past, including a room devoted to some really beautiful formal Mexican clothing, an area with historic medical equipment (including an iron lung), and displays of memorabilia from Deming’s public schools through the years.

This cart was owned by Leonardo Reyes, who sold hot tamales in downtown Deming from the late 1930s to the early 1950s. The tamales were kept warm in the cart’s crock with heated bricks in the crock’s bottom. Note the hard rubber tires. I would normally have cropped out the display cases of German nutcrackers in the background, but this perspective, I think, gives one a better appreciation for the diversity and scope of the Deming museum.

The museum also has an extensive collection, both inside and outside, of military equipment dating back to before the U.S. Civil War. I’ll write about that collection in another posting.

The Deming Luna Mimbres Museum was a great visit for us, although, to be honest, it was a little overwhelming in some areas. I thought I had taken pictures of a display of dozens upon dozens of buttonhooks (again, I’m not kidding and I could definitely be undercounting), and that’s what I was going to end with, but I guess I didn’t get any photos. It’s unfortunate. While I was there, I wondered – a lot – about who would find some of these displays of any interest. But I realized that’s exactly why museums like these are so important: you’re pretty much guaranteed to find something of interest to you, and particularly you, whether that’s fire engines or commemorative Jim Beam whiskey decanters or geodes or ancient Macintosh computers or a copy of the Braille edition of Playboy magazine (again, not kidding) or German nutcrackers or horsedrawn hearses or iron lungs (the iron lung was stationary, not horsedrawn) or barbed wire (I actually do have an interest in barbed wire) or buttonhooks or Native American pottery. Everyone has their particular interest(s) that are absolutely appropriate for curating exhibits (except for dolls – there should never be dolls on display). I recently read of the existence of an International Jim Beam Bottle & Speciality Club (IJBBSC). It has more than 150 affiliated clubs and more than 5,000 members. I hope some of those IJBBSC members make it to the Deming Luna Mimbres Museum, because let me tell you: there’s an impressive collection of whiskey decanters to be enjoyed.